I have now seen Emily Wilson’s BBC adaptation of The Pursuit of Love three times in its entirety. The first time was on a whim, just after its release, as a friend and I brainstormed what to watch together that night. I hadn’t read the novel and had barely heard of Nancy Mitford. Soon, I was re-watching all three hours of the series with other friends, eager to share its close and loving portrait of a female friendship (and, equally, eager to share Andrew Scott’s performance as Lord Merlin).

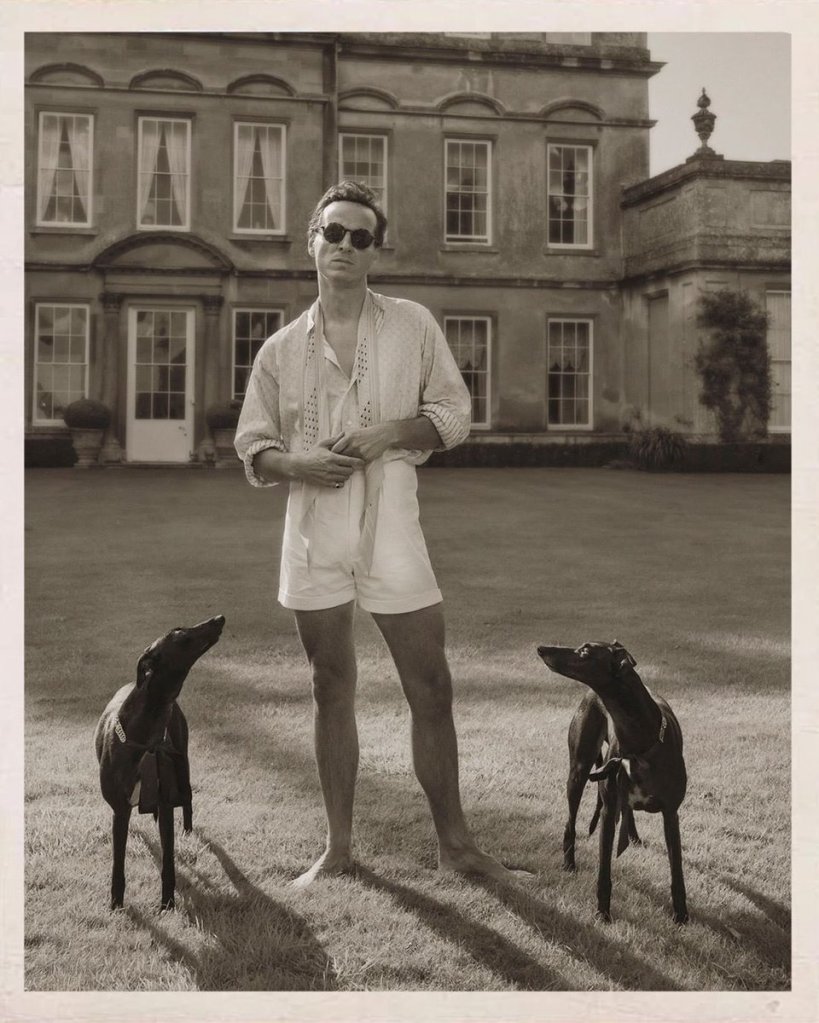

The performances here are really pitch-perfect, and I don’t know how the series would have worked without their tonal precision and joyful relish. Andrew Scott is the standout among the supporting cast, offering a spiritual reprise of his astounding turn in Present Laughter as Gary Essendine. (Essential viewing – every day that the National Theatre Live recording remains unavailable is unbearable.) Lily James delivers a powerhouse performance as Linda Radlett, and this turn marked the first time that I found myself thinking, oh, okay, she has serious talent. You can’t throw a stone in a British period piece these days without hitting her, but The Pursuit of Love is the first time I’ve fully bought James as her character, in that fully-converted way that makes you uninterested in any other interpretation of the role. She embodies Linda Radlett so fully, bringing all of the energy and charisma that this sort of character requires, and melts into the character seamlessly throughout the different periods of her life. I could have watched her impersonate Linda for many more hours and never felt bored.

The series is not bashful about its core themes. The double protagonists, Linda and her cousin Fanny, have multiple speeches and conversations exploring their sense of feeling trapped within the roles available to women, and regularly express their deep love for one another. I’ve just finished reading Big Friendship, and can’t help thinking of it as I reflect back on The Pursuit of Love. This series’ plot often revolves around the two women’s love lives, but their love is the overarching story that the series is telling. It is their bond which we see strengthened and tested, their conflicts which drive the series’ tension.

My favorite moment in the series comes in the second episode, when Linda is far away from home (and Fanny), having followed her second husband to work in a Spanish refugee camp in France. She is approached by another woman, and they talk briefly about the men they’ve left behind before focusing on their real heartache: the best female friends who are far away. They take out the fading photos that they carry with them, showing each woman standing with their friend, just the pair of them, younger, together. Two of the times I watched this scene, I cried.

Most of the times that the characters explicitly discuss their predicament as women, the series handles it well, with a core of human believability that sells the dialogue. Fanny’s constant wavering over her satisfaction with her life is highly relatable, as she wonders should I have done more? could I have had more? while she weighs the joys of mothering and marriage against their many frustrations and inadequacies. Though she takes to wifehood much better than Linda does – as a “sticker” rather than a “bolter”, in the terms of the show – Fanny does not come across as the sort of woman who is suited to the time she was born in. (This reminds me of an interview I read with the female stars of Hamilton. Asked how their characters’ lives would have been different if they’d been men, Renée Elise Goldsberry, who played Angelica, spoke about how the elder Schuyler sister would have excelled as a great thinker or politician herself. Phillipa Soo, playing Eliza, delivered an answer that has haunted me ever since: “I think she probably would have gotten less done if she were a man!”) No, Fanny is not fully satisfied, but neither is she entirely miserable. Her self-psychoanalyzing at her husband as they read in bed rings especially true – as does his nodding off after providing a reassuring but insufficient answer to her questions. Alfred is an imperfect husband, but their relationship is still one that brings contentment to Fanny, and it receives a touching denouement when Alfred visits her after the war has broken out. For nowhere near the first time, they discuss Fanny’s conflicted feelings about her life, and once she has gotten that off of her chest, she looks up at her husband. “I’m glad you’re not dead,” she says, this simple statement proving more true and touching than any great declaration would have been. (I am now, as always, thinking about the lyrics to Being Alive from Company.) They embrace, eventually making love, and it’s very sweet, and very human.

This ambivalence about romantic love runs throughout the series, including the famous final line (preserved from the book) as the other Radlett women discuss Linda’s affair with her third lover, Fabrice.

FANNY: I do think Linda would have been happy with Fabrice. He was the love of her life, you know.

THE BOLTER: Oh darling, one always thinks that. Every, every time.

(Characteristically, the women begin laughing, and it is that note we end with – always, in The Pursuit of Love, its undercurrents of cynicism and melancholy are met with light-heartedness and camaraderie.)

The Pursuit of Love does not make a case about the strength of Linda and Fabrice’s bond. Maybe he would have stayed with her until their old age; maybe he wouldn’t have. This world could contain either possibility, and does not seek to invalidate Linda’s feelings either way. The closing line dances along the edge of these possibilities, offering a cynical wink paired with a loving and hopeful smile. Wherever the journey of life takes its characters, The Pursuit of Love is ready to delight in the ride.

There was one sour note in the final scene. Very close to the end, Fanny’s Aunt Emily delivers a monologue that is so on-the-nose it nearly breaks the third wall with its cloying tone.

EMILY: Well, let’s hope that in years to come, these boys’ granddaughters can be more than just a bolter or a sticker, or a Linda or a Fanny, and decide who they are irrespective of who they marry.

The series had done so well up to this point to get the balance just right, staging conversations between characters that dealt with this central theme without standing directly on top of a soap box. One of my favorite such moments came earlier in the same episode – the moment that, to my mind, stands as the best example of the series delivering its thesis statement while also providing an important character moment between Fanny and Linda, as Fanny berates Linda for the way her self-centered choices have caused her loved ones strain over the years.

LINDA: Fanny, sometimes I don’t think we’re born women at all. It’s like your wings get clipped. And then everyone’s so surprised when you don’t know how to fly.

It’s almost too much, but Lily James sticks the landing, as both women sit in this moment of searching, unable to quite grapple with the ways they feel out of control over their lives. It’s a gorgeous moment. We don’t need Aunt Emily to spell it all out again in remedial fashion a few minutes later.

Aunt Emily’s speech was so inexcusable I wondered if it came from the original novel – that would at least explain why Emily Mortimer would have insisted on keeping it in. I’d gotten the sense, just by watching the series, that much of the zinging dialogue and humorous asides must have been lifted directly from the novel’s pages. When I picked up a pocket-sized copy of The Pursuit of Love from the bookshop, I saw the aforementioned final exchange of the series emblazoned across the back cover. But within the text, the rest of the conversation – including Aunt Emily’s speech – was nowhere to be found.

While my instincts had been right about much of the dialogue and narration, I was surprised to find that most of the moments I’ve outlined above – the ones that really struck me, and dealt directly with gender – weren’t in the book at all. On the whole, commendation is due to Emily Mortimer for her adaptive work here. With the one major exception, she did an incredible job of picking up the threads of these themes from the plot and laying them on the surface with new dialogue. Mortimer also fleshed out the role and character of Fanny quite a lot, inserting the novel’s narrator into scenes that she merely describes in the novel, and giving her an inner turmoil to match the outer turmoil of Linda’s drama. It’s the right choice for a series that presents them as dual protagonists, instead of subject and storyteller.

It’s worth noting that the novel doesn’t come across as uninterested in the themes of women’s inferior place in society – it just, somewhat predictably, isn’t offering explicit, third-wave-ready self-examinations by its characters. Instead, it offers a feminist perspective simply by telling the story that it does: one that centers on women’s lives and offers sympathy, not judgment, for the choices they end up making from a limited set of options.

In the series, Mortimer brings this dynamic to the forefront in a scene where Fanny gets to meet Fabrice, and comes away from the lunch converted both to his quality as Linda’s lover and the quality of Linda’s life overall.

FANNY: In books, girls like you always end up dead, Linda. I was so worried. But you’re not Madame Bovary or Anna Karenina. Life isn’t books. In fact, you are the most incredibly alive person I’ve ever met.

LINDA: Oh, well, you know, Fanny…someone should write a book about me. And give it the most tremendously happy ending.

The dialogue veers toward the third wall but sticks the landing, in part due to the drunken slurred deliveries. (Who among us hasn’t come around to a friendship epiphany on the back of a very boozy brunch?) Later in the series, Linda’s sister Louisa declares, “You should be the one to write the love story, Fanny.” “The one with the happy ending,” Linda specifies. “And I’ll sell millions of copies and get filthy rich, and Alfred will have to suffer the indignity of me paying for him in restaurants,” Fanny replies with a laugh. This comic turn keeps the moment from becoming too neat and saccharine, though it certainly flirts with the precipice. (As a side note: while this might inspire viewers to assume that Nancy Mitford was a real-life Fanny to another Mitford’s Linda, in reality, Nancy was the one who travelled to the refugee camps of the Spanish civil war with her husband and later fell in love with a hero of the French resistance. Though it was a different sister who ran away with a communist, and yet another one who married into a family of English fascists.)

While the novel does not feature the scene of Fanny and Linda’s boozy brunch and drunken conversation, it does capture the rebellious spirit of Fanny’s observations simply by telling the story of Linda Radlett in a sympathetic light. She’s a woman who leaves her unfulfilling marriage for one affair, and then another, and it never suggests that she’s made an unforgiveable mistake or that she’s a moral black hole. It doesn’t pretend that her life is bliss or that her choices were morally righteous in an uncomplicated way, either. It just presents her from the view of an adoring best friend, and allows us to share in the love that Fanny feels for her.

The Pursuit of Love’s open-minded approach to sex also struck me as unusual. Sure, explicit sexual content is par for the course in prestige TV dramas, but a 17-year-old female character in approximately 1930 declaring herself “obsessed with sex” in a way that’s treated as almost mundane certainly isn’t par for the course in period entertainment. The original novel doesn’t get into sexual details, but it makes it clear that its characters are having sex, and this sex isn’t imbued with the inherent danger and tragedy that so often accompanies female bildungsromans. Somehow, this tale that ends with a woman dying in childbirth avoids feeling like a morality play. The death is treated as what it is – a tragic fluke of health – not as a culmination of a character’s spiritual fate. The character’s love of life, her open-armed approach to new experiences, the fundamental alive-ness that Fanny speaks of – it makes the tragedy that much sadder. The death comes as a blunt shock in the book, moments away from the final line, with little build-up and little reflection afterwards, arriving folded between warm, comedic moments. Such is life.

I’ve been highlighting conversations that exist in the series and not the book, but the opposite situation happens from time to time as well. Less often than you might imagine, though – the novel clips along, precise and episodic, so much so that, reading it after the series, I found myself encountering all the major beats from the show one after another without much fluff in between. It was a bit of a jolt to come across any exchanges that had not made it into the series, at least in part.

One of these moments is a conversation near the end of the novel that, in the absence of monologues about women’s roles, offers an alternative thematic statement. Linda and Davey are discussing how future generations may look back on their era.

‘It’s rather sad,’ she said one day, ‘to belong, as we do, to a lost generation. I’m sure in history the two wars will count as one war and that we shall be squashed out of it altogether, and people will forget that we ever existed. We might just as well have never lived at all, and I think that’s a shame.’

p. 199, Penguin Essentials, 2018

There’s no equivalent moment where this point is made in the show, but the series struck me, upon the first viewing, with its vivid sense of what it must have felt like to be a young person living your life as you felt the world teetering on the brink of global disaster. This is now a familiar feeling, after all. And I found it so odd, and striking. There is a whole lot of art out there about World War II, but I hadn’t encountered anything before that captured the feeling of the looming building-up, over years, at a distance. This is a story of young people trying their best to live their lives to the fullest, in spite of the gathering clouds – self-interested, near-delusional at times, yes. I don’t know quite how to describe it. In so many of the stories set in World War II, you encounter characters who seem utterly of the situation, defined by it, fitted to it. But here they just seem like people whose lives would naturally have carried on in a particular direction but for the war. World War II happened to them. It knocked their lives off course. And that’s what it feels like when a massive historical international catastrophe arrives at your door. You keep trying to inhabit your life, as yourself, for as long as possible. And then you carry on as best you can.

During the first wave of Covid in the UK, locked down and at a loss, I found myself re-watching the JFK assassination arc from Mad Men. These episodes masterfully present the ways a shared historic moment of tragedy can seep into individuals’ mundane lives, their own personal dramas. Just after the 2016 election, I put on Children of Men when I felt a similar craving. (We also watched Contagion during the March lockdown, but it’s less of a stretch to see the connection with that one.) Whatever thread I felt pulling me to those stories, it’s here again, too. There’s a shot in the series where Fanny’s train is stopped on her way home from London as the air raid sirens go off, and her voiceover tells us that the war has finally reached them. It made me think about those first press conferences from Downing Street. You can’t picture these things happening. And then they happen.

The Pursuit of Love captures this surreal mood, just as it captures the particularities of its characters. Nancy Mitford pulled liberally from her own life, of course, and as I read the novel I was struck by how faithfully it seems Mitford had transcribed the personalities of such fully alive people. People will not be forgetting that they existed, as it turns out – even if it’s just bits and pieces of the actual human beings that make it into the characters. A turn of phrase here, an idiosyncrasy there. Some of it must be illusion; still, I’m grateful to have this fictionalised record of it all, and envious of the fellow travellers Mitford observed and immortalised. What a gift, to be captured in your full humanity in a book like this, which simply captures the delight of knowing you. Another book could have made Linda, flighty and self-centered, into a monster; Mitford allows her to be adored for herself. (In the series, Lily James’ winning performance certainly helps in this regard too; when Emily Beecham as Fanny describes how she could never stay mad at Linda after half an hour in her company, I completely understand.) The Pursuit of Love pulses with a central fondness, a tone of delight and amusement at the strange loveliness of being a person. There is a melancholy here too, and a hedonistic streak, which makes the entire package rich and satisfying. Life is never simple here, but it is still sweet.

Maybe it’s not a huge surprise that The Pursuit of Love charmed me so completely. After all, my ultimate comfort watch is Emma Thompson’s Sense & Sensibility. But despite The Pursuit of Love’s superficial similarities with many an Austen adaptation (one girl, blonde, is reserved and dutiful; the other girl has high spirits and willfulness!) it also brings several fresh ingredients to the table: the relative openmindedness about extramarital sex; the sense of impending global catastrophe; and the absolute centrality of the female bond as the core of the story, much more important than the romances themselves.

Also, it gave us this image.

Written 21 July 2021

For that full interview with Renée Elise Goldsberry and Phillipa Soo: https://www.playbill.com/article/a-womans-world-hamiltons-leading-ladies-the-schuyler-sisters-on-being-the-kardashians-of-the-1700s-com-360665

Leave a comment